One page TTRPG prep

I’ve been running table top role playing games for over a decade on and off, and I’ve settled into a prep routine. It’s heavily borrowed, if not outright stolen from other GMs on the Internets, and I encourage you to steal and adapt what I’m doing as well. If I had to guess, this way of preparation is stolen directly from the Lazy GM’s table.

I’ve learned that in order to run a successful session, I need to prepare the following:

- Discoveries: What my players need to discover.

- Scenes: Where things happen.

- Clues: Some thoughts on how to expose the discoveries.

- Key NPCs: Some names and primary aspects of non player characters.

- Enemies: A few stat blocks or references to enemies.

And all of the above fits on a single page: I find it enough to run the session while providing player freedom without having to completely invent everything on the fly.

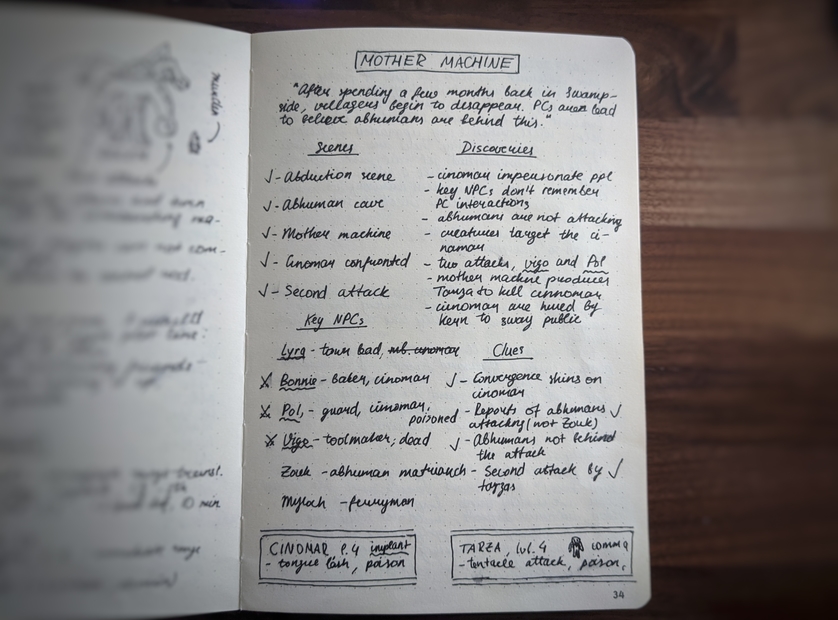

Here’s an example for a Numenera game I ran a few weeks ago, where I adopted the idea behind the “Mother Machine” module from “Explorer’s Keys: Ten Instant Adventures for Numenera”:

In this example, the village under players’ protection is attacked by “tarza”, never before seen monsters. For historical reasons, my players are initially expected to blame a neighboring tribe of abhumans for the attack. The monsters are in fact part of a defense mechanism which is attempting to exterminate so-called “cinomar”: doppelgangers who are impersonating some of the villagers.

Discoveries

This section cover key information and plot twists, and it’s the one I start with. I use it as a tool to outline the adventure, and it’s helpful to refer to if I get stuck.

These are the details players should unravel throughout the session, and I usually check them off as the players find them. In fact, you’ll see I check off most bullet points on the page as the session plays out.

Although, now that I’m looking at the example I provided, the discoveries are not marked. I guess I’m not very consistent.

Scenes

This is the primary tool I use during the game. Scenes outline encounters - be they social, exploratory, or combat related. Scenes help me form a general idea about locations the adventure will be taking a place in, as well as some of the key action sequences.

I often use scenes to help me control pacing: If I’m running a 3 hour game with roughly 5 scenes planned, I know to hurry up if I haven’t gotten to any of them at a one hour mark. It’s often a good time to narrate a time skip, tie up an ongoing investigation, or suggest a direction for the party to move in.

Now this doesn’t mean that the adventure is limited to these scenes. If (or more accurately “when”) the adventure goes off rails, I reskin these scenes or use them for an inspiration to quickly throw together a new scene.

Clues

Clues are ideas for how to surface discoveries. These are not strictly necessary if you’re really creative, but if you’re anything like me - these are a godsend.

Clues are concrete ways for players to discover plot points outlined in “Discoveries”. “The assassin had a letter signed by the big bad”, or “The drunken sailor lets slip about a cult in the town”. I aim for one clue per discovery, but it’s not a hard rule.

The list should not be exhaustive, and should not be strictly followed - I treat this section as an exercise in creativity. I find it more impactful to try to come up with clues as I play – players often search in places I haven’t thought of - so I place the clue to a discovery wherever the players are looking.

Key NPCs

This is a list of key non player characters relevant to the game. I try to keep number of named NPCs low to help my players remember them better, and I try to use as many recurring NPCs as humanly possible.

I usually add an aspect for each of the NPCs - a short description in a few words, something that makes them stand out in some way.

This list doesn’t have to be exhaustive – you’ll probably want to use the running list of NPCs for your campaign as a supplement for unexpected recurring characters, and a list of pre-generated names for unexpected encounters.

Enemies

The last thing is enemy stat blocks for quickly referencing if (again, “when”) a combat breaks out.

For Numenera, these are not particularly complex - most enemies are described by a single number and a few key things about them. I’d imagine for D&D and other combat focused systems you’d want to put a bit more effort in making sure you’re building balanced combat encounters, so that would warrant a section of its own.

I tend to spend a little under 20 minutes on all of the above, and I get to use it in three out of four games – the fourth one tends to go off the rails completely, and I’m okay with it. Without investing as much time into prep, it’s easy to be taken on a ride by the players.