-

Japan's etiquette is weird

We went to Japan last month, and I’ve finally found the time to put together my notes. I’ve been meaning to write this for a while - my scribbles have been sitting in a text file, judging me.

We spent time in Ho Chi Minh (or Saigon if you’re old) before heading to Tokyo, and the contrast was so striking that I can’t stop thinking about it. Both incredible places, both completely different in ways I find genuinely fascinating - and completely hilarious.

Japanese people love to queue. I say this with admiration - it’s a cultural commitment I find both impressive and, in its most intense forms, comedy gold. Food? Queue. Taking a train? Queue. Elevator? Believe it or not, queue. I’m half convinced there’s a queue somewhere just for the privilege of standing in another queue.

And oh, the “close door” button on elevators. I witnessed something beautiful in Tokyo: the unmistakable rapid-fire mashing of that button the moment someone steps inside, even when - especially when - they can clearly see me approaching. It’s not malicious. I don’t think it’s even personal. It’s just… commitment to efficiency, extending all the way down to shaving those precious three seconds off the elevator door’s natural rhythm. Dude. I can see you. I’m right here.

Just look at the wear pattern on these elevator butons:

That’s what most elevators looked like.

The subway has a similar choreography. People pushing past you with practiced, almost apologetic urgency. Same with the konbini - if you’re in someone’s path to the onigiri section, you will be navigated around like a minor obstacle in an otherwise frictionless system. It’s nothing personal, you’re just in the way of the system.

Here’s what really struck me about Tokyo: you can go an entire day without having a meaningful interaction with another person. And I don’t mean that in a sad, lonely way - I mean it as a genuine observation about how thoughtfully everything is designed.

Restaurants have ticket machines where you order and pay before sitting down. Your food arrives. You eat. You leave. No one needs to talk to you. No one wants to talk to you - and that’s not rudeness, it’s infrastructure. The system handles everything. The mother’s rooms were cleaner than our own house (and I mean that literally - I looked around one of those nursing rooms and felt personally called out by my own bathroom at home). Everything has a place, a purpose, a queue.

It’s impressive. It’s hyper-functional. And after coming from Vietnam, the contrast was jarring.

In Vietnam, you cannot avoid interacting with people. It’s physically impossible. Every transaction feels impromptu, like you’re the first customer they’ve ever had and everyone’s figuring it out together in real-time.

Paying a bill at a restaurant? That might involve three people, a calculator that may or may not work, and a vague sense that the total is more of a collaborative suggestion than an established fact. “How much?” “Uh… let me ask my cousin.” This is not a criticism - it’s delightful. There’s a warmth to that chaos.

Service in Japan is polished to perfection, almost rehearsed - which makes sense, given the cultural emphasis on hospitality. In Vietnam, it felt more like someone’s aunt decided to help out at the family restaurant. Less professional, maybe, but somehow warmer? The friendliness wasn’t performance, it was just… how things were.

Traveling with an infant is exhausting in ways I couldn’t have predicted, but it’s also like carrying around a small social barometer. You get to see how different cultures engage with kids, and the contrast between Tokyo and Ho Chi Minh was striking.

In Ho Chi Minh, my daughter was a celebrity. Everyone wanted to hold her, talk to her, feed her something we probably shouldn’t let her eat. The warmth was overwhelming - chaotic, often not always hygienic, but deeply human. Strangers cooing at her, shopkeepers waving, someone’s grandmother stopping us to admire the baby. Human connection wasn’t optional - it was woven into the fabric of every interaction.

Tokyo was different. Not cold, exactly. Just… distant. People are exceptionally polite, but there’s a respectful bubble around families. No one’s stopping you on the street to admire your baby. Which is fine! Privacy is a gift, especially when you’re tired. But it’s noticeable when you’ve just come from a place where your kiddo was treated like a visiting dignitary.

In Japan, you can live in a world of seamless, frictionless interactions. Machines handle payments, apps handle navigation, and the physical infrastructure is designed to minimize the need for human contact. It’s efficient, clean, and just really cool.

In Vietnam, the infrastructure almost forces you to connect. Nothing is fully automated. Everything requires negotiation, conversation, a smile and a nod - it’s messy. It’s inefficient by lack of design. And it’s incredibly human.

I’m not saying one is better than the other - that’s too simple, and frankly, kind of reductive. But I do find myself wondering what we optimize away when we make things frictionless. What do we gain, and what do we lose? Japan’s systems are a marvel, but they also create a world where you can be surrounded by millions of people and have a difficult time connecting with them. Vietnam’s chaos forces connection, for better or worse.

Or maybe I’m taking huge leaps in judgement based on a few weeks in countries where I didn’t speak the language and barely knew anyone.

It was a good trip. We had a great time, even if traveling with an infant is a whole thing. We’ve been unable to do many fine dining establishments because of the kiddo, and honestly? We felt much more comfortable and relaxed eating at a regional equivalent of Denny’s. It’s nice not to feel too bad when your baby starts happily throwing food around.

Maybe next time we bring parents along. Outsourcing some of the infant-wrangling sounds appealing.

-

The illusory truth effect

I’m a bit late with this, but here’s an interesting headline: “Liberal arts students have lower unemployment rates than computer science students according to the NY Fed”. It’s a headline I saw early last year, took a note to read further, and just rediscovered the headline when cleaning up my notes.

Here’s an article from The College Fix from June 20, 2025: Computer engineering grads face double the unemployment rate of art history majors. In the article, the author claims:

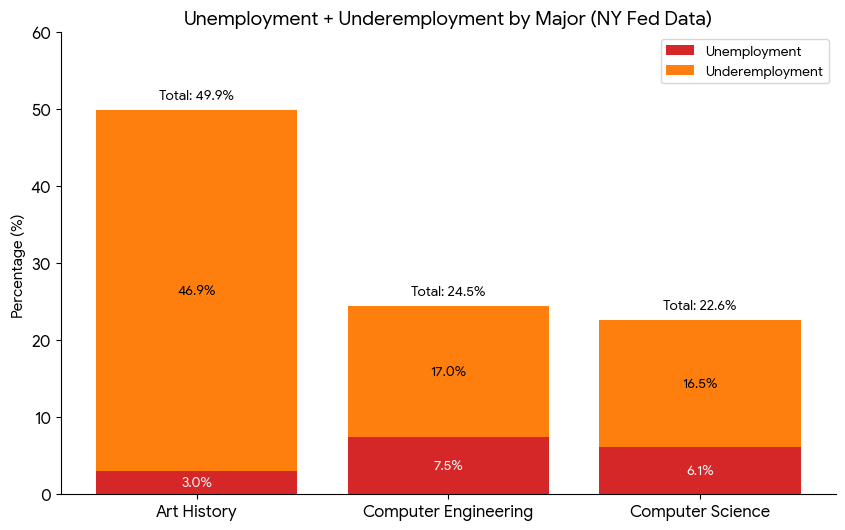

The stats show art history majors have a 3 percent unemployment rate while computer engineering grads have a 7.5 percent unemployment rate. Computer science grads are in a similar boat, with a 6.1 percent rate.

Ok, let’s find if this lines up with what NY Fed says:

Major Unemployment Underemployment Art history 3% 46.9% Computer engineering 7.5% 17.0% Computer science 6.1% 16.5% Oh, what’s that number next to “unemployment”? Uh-oh. Underemployment accounts for people working in a job which does not require a bachelor degree. This means that a computer engineering graduate is working a tech job, while an art history major takes up work in a fast food restaurant. And all of a sudden, the picture shifts. 17% of computer engineering majors were underemployed, while a whopping 46.9% of art history graduates weren’t utilizing their degree.

This article is one of many, which cherry-picked data from the NY Fed and made outrageous claims. Further, the data is from 2023, which the article above mentions near the end, in passing. That’s a pretty relevant bit, for an article written in 2025, isn’t it?

For me this brought up a question of digital hygiene and how the headlines I see affect us.

I have seen this headline many times throughout the year - I never read through content, but over time the headline stayed in my memory.

The illusory truth effect is the cognitive bias where repeated exposure to a statement makes it seem more truthful, even if it’s known to be false.

I really did believe that CS graduates had lower employment than art history majors. Don’t get me wrong, the job market for newgrads is oh-so-brutal, and the future prospects are murky. Which probably made it easier to believe such an outrageous claim.

Yes, disproving the headline took all of 10 seconds, but how many headlines do you see a day? What other misinformation cements itself in your head?

And ultimately, is it better to limit access to such information, or - however impractical - try to verify everything you see?

-

I shouldn’t have bought that keyboard

A little over a month ago I bought a keyboard for my phone. Here’s what I wrote:

I’ll follow-up in six month to year to see if that’s just a gimmick purchase. Or maybe I end up drafting up my next book using this thing - we’ll just have to see.

Well, it was a gimmick. It’s a great keyboard, and I’m sure niche use cases will come up here and there, but… yeah, a gimmick. There I was, on our family trip to Japan and Vietnam, excited about all the writing I might do from a hotel room, or maybe in a coffee shop, or even on the long flight.

But here’s the thing, we travel with an infant. Yeah, that’s an important part I kind of glanced over. There really isn’t that much free time to write when you either entertain, feed, or sleep the little potato, and when you’re not doing that - you just want to lay down, or maybe talk to your partner because you two haven’t had uninterrupted conversation in months.

But even beyond that, I massively overestimated my own desire to write when I’m on vacation. I love writing, and it did find a few occasions to plop open the device and jot down some notes, but ultimately writing is work. Rewarding work I enjoy, but it’s still work. I don’t like to work on vacation. I like to chill.

With hindsight, as I’m reading the excited mini-review for my little ProtoARC XK04, I can clearly see how naive I was, and how I fell for the idea that all I need is a sleek little keyboard, and I’ll write more! I will be oh-so productive!

My partner and I often talk about the barrier to doing things (tm) and how it interacts with the stuff you buy.

I don’t really need a fancy pair of running shoes to start running. And I don’t need a fancy notebook or a nice keyboard to write. Yes, it’ll probably get me excited to get into the hobby, but this type of excitement passes quickly.

A few years back - half a decade or so - I lived a little too far from work to bike. A little too close to justify driving. My wife and I decided we’ll get me an ebike, ebikes aren’t cheap, or at least they weren’t back then. We got one, and it was exactly what I needed: a little more power to make my hilly 30 minute commute by bike a no-brainer. I biked 5 days a week, and I did so for years until we moved.

Maybe that’s why it’s so hard to tell when something is the right tool for the job, or ultimately just a gimmick and a waste of money. Companies have gotten very good at selling you a belief in a version of yourself - you don’t buy an item, you think about who you will become (with a help of said item). I think of myself as somewhat frugal and prudent with money, but this just comes to show how easy it is to fall into that trap.

So yeah, I didn’t write more because I bought a little keyboard. But I am writing more (twice a week for nearly a year now) because I made a commitment, because I enjoy the creative process, and because it makes me feel good.

-

Looking back at 2025

2025 was a crazy year - a good kind of crazy for once.

My daughter was born, and she’s pretty cool. Adjusting to life with an infant wasn’t easy, but we took on the challenge gladly - we lost our firstborn, and we’re grateful for every inconvenience or a sleepless night. But yeah, life won’t ever be the same.

I took a lot of time off work to be with my kiddo, which was great for my mental health. This is the longest I haven’t worked in my adult life, and believe it or not - not working is nice, and I’m hoping I’ve been trying to keep this optimistically detached attitude as I got back to work throughout the year - with mixed success, but it’s nice to know what the north star feels like.

The space to not work opened up room for other things. I got pulled into writing - a lot more than before. This year I published far north of 100,000 words across this and my gaming blog - publishing weekly across both outlets. That’s a thick novel worth of words, and while not everything I wrote was great, I enjoyed having to come up with new topics, having to get my thoughts out on paper, and getting to experiment with various voices as a writer. 4 of my articles got boosted on Medium this year (which I thought was pretty cool), and I had some incredible conversations with folks in email and comment chains. I especially enjoyed jotting down decades worth of unfinished thoughts about games - gaming is a hobby I deeply enjoy.

We’ve done a few international trips - namely to Japan and Vietnam, and enjoyed both. Traveling with an infant was fun and weird, and I’m excited for even more travel next year. I also got to enjoy building different relationships with my parents and my in-laws, since we now primarily engage with them from the lens of having a kid. It’s fun, it’s frustrating, it’s novel.

All of this - alongside many conversations with family and friends - really brought on a philosophical shift. More appreciation for the impermanence of things. Life won’t be simpler than it is today, things will only get more complicated. And that’s fine. I get to appreciate the way life was before, and I get to enjoy the way life is now. More complicated, more messy, much more full of life.

-

Home is where my stuff is

When I was in my 20s, decluttering was easy. I didn’t have a lot of stuff. I came to the US with a single suitcase, and I mostly kept my stuff contained to that suitcase for years. It was nice - every time I’d move when renting rooms (which was often), I’d go through all my stuff, put it back in the suitcase, and be back on the move.

My mom lived through the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which instilled a scarcity mindset - something I naturally inherited. You don’t own too many things, you take care of what you own, you don’t throw stuff away. Stuff was hard to come by, so you respected it.

The irony is that this mindset both prevents accumulation and makes decluttering harder. You don’t buy frivolously, but you also don’t discard easily. Every object earned its place.

I slowly started accumulating stuff. First, it was the computer. My love of both tech and games is no secret, so I upgraded from a tiny netbook into a full-blown gaming PC. It wasn’t anything to write home about, but it was big enough that it would no longer fit in my suitcase. There was a monitor too, so two things that I had to have. It was the first time I needed help moving - and my last landlord was nice enough to help - a suitcase, a PC tower, and a monitor.

I still didn’t have too much stuff, and a dedicated PC really was a great investment for a gaming enthusiast like me. I got a bicycle too, but that was really a transportation method, and while it was yet another thing - it made me healthier and opened up the city around me.

Clutter escalated once I rented an entire place to myself. All of a sudden I needed furniture, moving up from prefurnished rooms. At first I lived in a tiny studio which didn’t even have a functional kitchen. A bed, a clothes rack, and a desk for my computer.

The studio was cramped and utilitarian, but I remember a specific kind of peace. Everything I owned was visible from the bed. No hidden boxes, no “I should really go through that” guilt. I could see all my stuff. I didn’t realize at the time that this was a temporary state - not a lifestyle I’d chosen, but a constraint I’d graduate out of. Minimalism is easy when the life is not yet complicated.

I won’t bore you with every place I lived in throughout my life, so let’s fast forward a decade. My wife, child, and I live in our house in San Diego, and have a lot more stuff now. Naturally, all the furniture, clothes for three, kitchen stuff (I love to cook), so many different things. There’s all the home improvement stuff - hey, gotta keep the paints, the brushes, the hammers and the drills. Need all of that to take care of the house we own. I have many more interests these days too - from miniature painting to, as of recently, 3D printing. All of the hobbies take up valuable space.

I had a director, Luke, who was complaining about business travel - and me, being a young tech professional, could not relate. He would say “Home is where my stuff is. I like my stuff.” And now that I have more stuff - ugh, I get it.

I go through annual decluttering, Konmari exercises (“does this bring me joy?”). But it’s hard, because buying stuff is really easy. A few clicks and tomorrow (or sometimes even today) there’s a box on your porch. Look, just last week I talked about a phone keyboard I bought. The friction is gone. The decision to acquire takes seconds; the decision to discard takes emotional labor.

Here’s what I’ve realized: every object I own is a fossil. A little sediment left by a past version of myself.

The gaming PC wasn’t clutter - it was proof that I’d made it, that I could afford something nice for once, that I wasn’t just surviving anymore. The drill isn’t clutter - it’s homeowner-me, a version of myself that 20-something-year-old me with his suitcase couldn’t have imagined. The 3D printer is current-me’s curiosity, an exploration of a hobby. The miniature paints are the version of me that finally has time for hobbies just for the sake of having hobbies.

This is why decluttering is so hard. It’s not really about tidiness. It’s about deciding which past selves get to stay.

That drawer with random cables? That’s “I might need this someday” me - the Soviet scarcity mindset my mom handed down. The programming books I’ll never open again? That’s a young programmer me from a decade ago. The fancy kitchen gadgets I used twice? That’s “I’m going to become someone who makes pasta from scratch” me. Aspirational me. He didn’t pan out, but he tried.

Some of these versions of myself are still relevant. Some aren’t. The hard part isn’t identifying which is which - it’s accepting that letting go of the object means letting go of that version of me. Admitting that I’m not that person anymore. Or that I never became the person I bought that thing for.

I don’t think the goal is to minimize anymore. I’ve read the minimalism blogs, I’ve seen the photos of people with one bag and a laptop living their best life in Lisbon. Good for them, I lived that life before - hell, I lived out of my car for a year. But I have a partner, a kid, a house, and more varied interests. All of which come with stuff.

I want to be intentional about which identities I’m holding onto and why. Some sediment is just dirt - clear it out, make space, breathe easier. But some sediment is bedrock (I’m not a geologist, I don’t know rocks). The one suitcase life isn’t coming back, and that’s okay. I’m in a different stage of my life: I look back at my “simple life” with longing, but I enjoy my life today even more - or maybe just differently. I certainly enjoy it in the way important to me today.

So now when I declutter, I try to ask a different question. Not “does this bring me joy?” but “which version of me needed this, and do I still want to carry him forward?” Sometimes the answer is yes. The drill stays. The 3D printer stays. The gaming PC - upgraded many times now - stays. And sometimes the answer is: that guy did his best, but I’m someone else now. Thanks for getting me here. Into the donate pile you go.

It doesn’t make decluttering easy. But it helps me make peace with the mess. The suitcase me is not coming back, and that’s probably for the best - he didn’t really have much of a life yet. I’ve got more stuff now. I’ve got more me now. I’ll figure out what stays.

It’s been 10 years since I first wrote about my experience with minimalism. Reading through it now - many of the story beats are similar, but the perspective changed. Funny how that works…