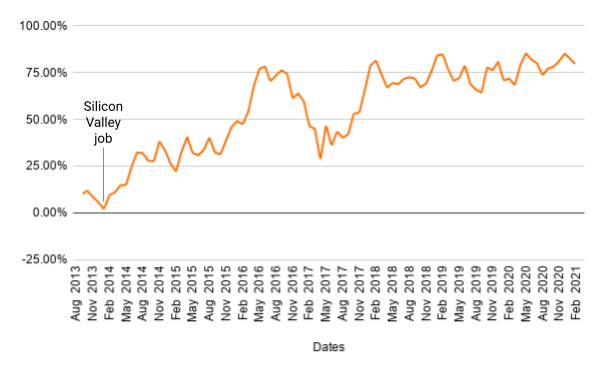

Savings rate plotted over 8 years

I just found my financial records going back to 2013!

I know that doesn’t sound exciting, but for someone who loves putting together spreadsheets this is a treasure trove of information! Well, maybe not a trove, but a sizable chunk of data. I only have two numbers for each month – income and expenses. But that’s just enough to calculate my savings rate!

(income - expenses) / income = savings rate

With this number I can trace a broad outline through the past 8 years of my financial life! I present my savings rate charted over the past 8 years:

It’s smoothed out using a 6 period rolling window, as it’s near impossible to see trends when plotting raw numbers.

This chart tells a life story: starting with a near 0% savings rate in early 2014, a dip in 2017, and a steady 75% from 2018 onward. Let’s trace my major life events!

By the end of 2013 I lived in downtown Philly and was working as a freelance software developer. Per-project pay was decent, but the gaps between contracts reduced the overall income. That, and being a sole breadwinner for a family of two – the funds were running dry and we were living paycheck-to-paycheck.

My then-SO and I had different financial upbringing. My ex-wife and I were both young when we got married, and we’ve never sat down and talked about finance – so I could only guess as to what her relationship with money was. I came from a household of a frugal single mother – we were never short on cash, but the expenses were low. In a rural community food was grown in a large garden, milk bartered from a neighbor, sweaters knitted.

I distinctly remember my partner not having more than a couple of hundred dollars in a bank account when we moved in together. On the other hand, by the time we got married I amassed a nest egg - nearly $20,000. Granted, it’s small in the grand scheme of things – but these were the savings I put together from working low wage jobs – before I learned software development.

You can see us deplete that fund by the end of 2013 and into early 2014. And paycheck-to-paycheck we lived.

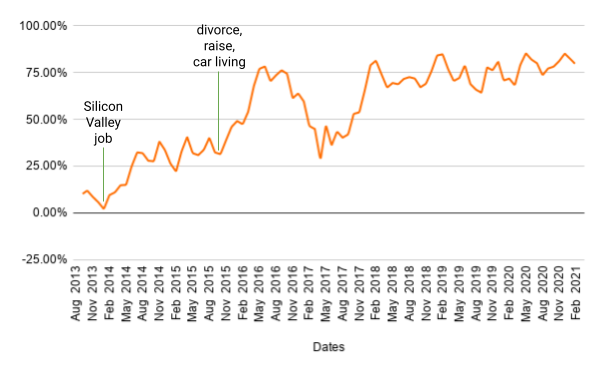

In January 2014 I was offered a position with a software company in the Silicon Valley. Things were looking up for our financial life! My then-wife and I moved to a Bay Area suburb.

It took some adjusting after living in downtown Philly. Both our income and expenses increased. Thankfully with the new job we found it harder to keep up with the increasing income: that’s where we settled for the 25% savings rate. A balance between frugality and spending habits.

A marital disaster struck at the end of 2015: my now ex-wife and I split up. What was a downturn in life turned out to be a financial upturn for me. My ex moved back with her parents, and I stayed in the apartment we were renting.

In a bout of coincidental timing, the apartment complex I lived in was scheduled for demolition. I had to move out and look for a new place. Instead, I decided to move into my car. I wrote about that in detail before, if you’d like to read about that.

This is when I became interested in the FIRE movement. If you’re not familiar, “FIRE” stands for “Financial Independence, Retire Early” (I like to think everyone is aware that this is a terrible acronym). The idea is to increase income, drastically decrease expenses, and invest the difference into index funds to live off of indefinitely.

Now that I had an idea where my money can work best, I had an easier time justifying increasing my savings rate. FIRE also turned increasing savings rate into somewhat of a game.

Finally, I negotiated a chunky raise at work. I was underpaid by the Silicon Valley standards, and “I like working here, but I need to be paid X or I quit” tactics worked. Having a reputation for being a high performer no doubt helped.

It’s not surprising that as a culmination of those events, this is where you can see my savings rate beginning it’s climb to a respectable 75%. Occasional spousal support would bump up the expenses, but not having rent to pay and a higher salary made it easy to absorb those expenses.

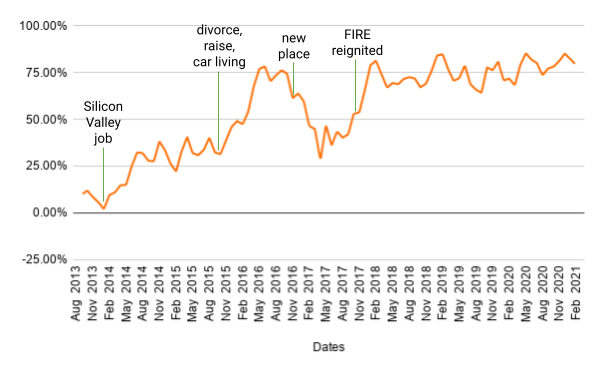

By the end of 2016 I got my dream job at Google, and moved into a new studio apartment. No, the big dip isn’t just a new place, but it’s strongly connected. I decided to make up for a year of living out of a single suitcase. There’s furnishing the new place from scratch, top of the line gaming PC, a VR headset, and so many things I didn’t need! I definitely went on a bender.

It took me a year to slow down. This is also where my then-girlfriend and now-forever-housemate became more open with me financially: I happened to meet another FIRE enthusiast out in the wild, completely by chance. She reignited my desire to live frugally. End of 2017 was marked by me donating and selling an ungodly amount of things I accumulated over this year, and returning to comfortable living within (or below, depending on how you look at it) my needs.

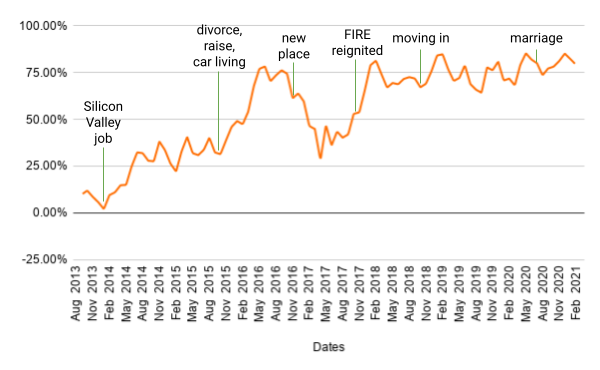

We moved in together by the end of 2018 and married in 2020. We still keep separate accounts for ease of accounting, and this chart only displays my data for the sake of my partner’s privacy (it’s less work to chart too). Overlaying my SO’s data after combining our finances doesn’t meaningfully change the numbers you see above.

It’s not realistic for us to push the savings rate higher without sacrificing the luxuries we enjoy - like travel or occasional high end dining. So here we are, at a comfortable 75% to 80% savings rate.

My wife and I earn 7 times more than I did when I was a sole breadwinner. Our joint expenses are 60% higher than what my ex wife and I spent 8 years ago. Both my wife and I are in a priviliged position to be high earners in a high paying industry. We’ve gotten extremely lucky where many wouldn’t have.

There’s no real purpose to this post other than sharing my journey. Hope you found something of interest!

Living at work

My first remote work experience coincided with my self-employment as a contractor. I was building a copyright enforcement service for a client in a year 2013. I lived in a one bedroom apartment in Philadelphia with my now ex-wife – a few blocks away from the city hall. I worked at a small standing desk (trendy!) in a corner of our little bedroom - by the closet.

I worked from the early morning and deep into the night at that desk. Sometimes I would look out of the window behind me. I would see an uninspired urban picture of roof tops of other four story colonial homes. And after a moment of respite it was back to work for me.

This was my first major foray into the world of self-accountability: I meticulously tracked the time spent working, billed the client per hour, provided in-depth breakdowns. The more I worked, the more I could bill the client – I had the incentive to put in as much time into work as possible.

So I did. I clocked in 80 to 90 hours of billable time a week. The checks with a before unheard of hourly rate kept coming, so I kept putting in the hours. Neither I nor my significant other had major professional experience. (To be completely honest we didn’t have much in the realm of like experience either). We kept on keeping on.

I thought about work during lunch. I was agonizing over the details when walking through the neighboring Rittenhouse Square. I would jump into late night coding sessions. As a young professional, I didn’t see the need to draw lines between my work and my life – my life was my work. There was no “me” without work.

That is until I burnt out. I woke up one morning, and something inside me snapped. I realized that I couldn’t spend another minute in front of the screen. I took a day off, and the feeling wouldn’t pass. I felt numb and overwhelmed at the same time. A day filled with my favorite video games - and I still felt that way. A day at a museum - nothing. I didn’t get better.

I invoked a force majeure clause in my contract. I transferred all the materials, sent the final invoice, and stepped away from the project.

I won’t talk here about the ways to fight burnout, because I didn’t know how to. I quit, took a break, and eventually moved onto another job. By the virtue of this happening early in my career, and me being rather young - I managed to “snap out of it” between jobs.

I wish I could share “the one thing” I did that helped - but there wasn’t one. I don’t remember how I took care of myself, and how I managed to get my head straight. All I remember that I felt discombobulated for weeks. And at some point the feeling went away. I couldn’t work during that time.

Time passed. I moved across the country to the San Francisco Bay area for a job with Google. My now ex-wife and I split up – it was a civil, but nonetheless a difficult divorce.

Around that time, I spent a year traveling across the United States. I lived out of my car and stayed in hotels while working remotely on my own terms. I established strict working hours and routines.

I would start my work around 8 am, without paying mind to the timezone I’d be in. I’d work out of coffee shops, coworking spaces, or even campgrounds. I’d always take a break for lunch. I’d wrap up work at 4 pm, and not a minute longer. Constant travel and change of scenery encouraged me to keep to my work hours. I had to weigh in staying past my end of workday versus going out and sight seeing a new city. The wanderlust always won.

The work was out of my mind after 4 pm. That was easy to do with an adventure afoot, but years later and the habit stuck with me. I don’t let thoughts about work slip into my day to day. My mind is my own outside of work.

That was a transformative experience, and it changed the way I see work. I know it’s trendy to say this, but I don’t live to work: I work to live.

Today, I work with some people who have never worked remotely before the pandemic. And I often hear a similar sounding sentiment: “never again”.

It makes me think about the time I was self-employed for the first time. Putting in 80 hour work weeks, and not having the awareness to understand how I was affecting myself and people around me. It created distance between me and my partner. I let the work spill into the time I had. In a way it made me less of an employee and less of person.

When the pandemic started I looked back to these memories. Google moved to continuous work from home model in March 2020. And I made a conscious effort not to slip into my early remote work days. I established a strict routine. Breakfast and lunch with my significant other (here’s some closure to my divorce). No deviation from “9 to 5”.

I established an area for myself to work in – I bought a sturdy desk and a chair from a used office furniture reseller. I make an effort to create not only mental, but physical separation from work. I wear office clothes during the day, and change once I’m done with work. I cook to distress after a long day. My partner and I adhere to scheduled date nights (we do leave room for spontaneity too).

That isn’t to say I didn’t slip over the past year: many times I stayed past an established time. I often started earlier than planned. And some days I would let work occupy my mind space as I’m relaxing with my better half. We’ve spent the past year working out of a one bedroom apartment. A bigger one than I worked out of 7 years ago, but still a one bedroom. It was difficult, and some days it still is.

But time and time again, I corrected the course and resumed my routine. During my soul searching adventure remote work was fun. Because this time working remotely is much harder. There are no sights to see. No new places to stay in. No novelty to look towards at the end of the day. Working from home in the middle of a pandemic is oh-so-difficult.

To be honest I can’t wait to be back in the office. But I’m also excited to work from home on my own terms. Because this isn’t what remote work is like.

How much does writing a book earn?

I write about Vim – a modal text editor – a lot. In fact, in early 2018 I was approached by Packt Publishing – what I’ve later learned to be a “quantity over quality” publishing house. Over the next 6 to 9 months I wrote a 300-page “Mastering Vim”.

It was a stressful endeavour, with a publisher rushing to meet internal deadlines and eventually sending an unfinished draft to print. There were many highlights too, like actually cranking out 300 pages of material, or getting to work with Bram Moolenaar – the creator of Vim himself. Now that a few years have passed and the book is at its 3rd edition, complete, and re-released – I’m a lot more happy with the result.

I can write a whole other essay about my experience working with the publisher, but that’s a horror story for another time.

I didn’t write to make money, but it’s nice seeing a couple of hundred dollars trickling in every quarter. Putting together spreadhseets is my favorite past time, so here’s a breakdown of my earnings from the time I wrote a book with Packt.

As of April 2021, the English version of my book has 14 reviews on Amazon averaging at 5 stars (that’s more than I would hope for), which likely helps keep the sales at a somewhat of a steady level.

I was signed into a default “16% of net receipts” contract, with a $2,000 advance given out to me. The advance was split into 5 milestone-based installments: the first preliminary draft, 6 preliminary drafts, the remaining preliminary drafts, the final drafts, and the publication. Although I didn’t urgently need the money, and the publisher may have just sent it as a bulk $2,000 payment after the publication.

Eventually I received a PDF for the first quarter of my book being sold… And here are the financials for Q4 2018:

| Print # | Print $ | E-books # | E-books $ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | $55.50 | 274 | $307.70 |

A whopping 363 dollars and 20 cents in royalties! I didn’t really think anyone would be interested to read the book, so seeing 284 copies sold I was pretty ecstatic!

Selling printed books seems to pay $5.55 per copy, while e-books only bring me $1.12.

Now I didn’t see any of that money, since I would have to “pay back” the advance. I know it’s called “the advance”, and I knew that I won’t be getting that first check in the mail – but it sucked a bit nonetheless.

After that I received some great news – my book was going to get translated to Japanese! During my last trip to Tokyo I made some friends who were interested in Vim as much as I was, and one of them - Masafumi Okura - decided to translate “Mastering Vim” into his native language. The legend found close to three dozen mistakes in my book too, and is solely responsible for the third edition of Mastering Vim!

Turns out the translation rights are expensive, and I’m getting my cut as well – $1,586.26! That’s more than the first quarter of sales!

Packt advertised my book for a few months or so, but they seemed to have quickly lost interest. I received my first 5 star review on Amazon though, which was great! I spent the next month refreshing Amazon reviews daily, after realizing that to be a path to acquiring a mental illness.

2019 came, and here are my next 4 quarterly statements:

| Quarter | Print # | Print $ | E-books # | E-books $ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 Q1 | 29 | $141.89 | 202 | $337.49 |

| 2019 Q2 | 15 | $77.53 | 71 | $194.26 |

| 2019 Q3 | 19 | $100.09 | 57 | $207.68 |

| 2019 Q4 | 23 | $118.55 | 117 | $255.17 |

I sold 86 print books and 447 e-books in 2019. You can see the higher numbers correspond to seasonal sales. Notice the prices for Q3 and Q4. E-books sold in Q3 pay me as much as $3.64 per copy, while in Q1 it’s a meager $1.67 per book. Print edition payout stays much more consistent.

Altogether, I earned $1432.66 from my first full year of selling “Mastering Vim”.

Here are my 2020 earnings:

| Quarter | Print # | Print $ | E-books # | E-books $ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 Q1 | 26 | $131.61 | 112 | $414.12 |

| 2020 Q2 | 22 | $106.67 | 77 | $379.61 |

| 2020 Q3 | 26 | $141.17 | 74 | $325.97 |

| 2020 Q4 | 45 | $236.69 | 166 | $458.07 |

That’s $1,533.38, a $100 more than in 2019. The patterns seem rather predictable, with Q2 and Q3 being slow, and Q1 and Q4 displaying a noticeable spike.

Finally, Packt offers service subscriptions – I believe the subscription is for the courses they offer, but I can’t say for sure. Payout per subscription is small, and I’ve earned $158.10 over the 9 quarters since publishing “Mastering Vim”.

Across $3,329.24 in book sales, $1,586.26 in translation fees, and $158.10 in subscriptions, this adds up to $5,073.60 over the 2+ years the book has been in print. Looks like it can make for a decent supplemental income if you write enough books, but I’m saying that based on a sample size of one.

Throughout this time, my earnings per copy average at $5.16 for a print, and $1.93 for an e-book (using weighted averages for quarterly sales).

And here’s the last number in this post – this one purely for fun. Based on the 16% royalty rate, Packt probably earned $31,710 from “Mastering Vim” so far.

The feedback fallacy

After learning about “Radical Candor”, I became obsessed with providing candid and compassionate feedback. I’ve been especially focused on the ability to communicate areas of growth for individual on my team.

And then a colleague of mine shared “The Feedback Fallacy” (published in the Harvard Business Review), which points to some research and outlines a few key problems why focusing on negative feedback might not be the best choice. Research shows that:

- people are bad at assessing other people

- we learn best with positive reinforcement

- focusing on shortcomings impairs learning

- excellence is specific to an individual

Like many pieces of business literature, it reads like an “all-or-nothing” approach (“negative feedback - bad, positive feedback - good”), and the most effective approach is likely somewhere in the middle. There’s a place for positive and negative feedback, and it’s the focus on positive reinforcement that I see as a primary takeaway from this article.

I’ve noticed that my assessment of others’ performance changes over time. It often depends on what self-help book I’m reading at the moment if I’m being entirely honest.

This piece made me think of the portrayal of successful people in media: there’s an inherent cultural belief that successful people know what makes them successful, and all you need to do is to follow in their steps! What is often omitted is a mix of luck, some talent or hard work, topped with another serving of being in the right place at the right time. Warren Buffet can probably tell you what’s the smartest thing to do with ten thousand dollars you have in your savings account. It’s unlikely that his advice alone will get you to his 98.2 billion dollar net worth.

It seems like once you get past basic competency, success identifiers seem unpredictable.

I attribute part of my professional success to having a reputation of a person who “gets shit done”. I naturally value qualities associated with that style of work. It’s only natural that I prioritize on communication and organizational skills when assessing the performance of others.

In fact, the article made me think about how I landed with the reputation as a problem solver. Every time I accomplished a project on time, owned the problem space, involved the right parties, or raised alarms early – I received positive reinforcement. People I worked with valued those qualities, and years working with those people shaped what I perceive as an effective work style.

Yet, this work style is effective for me, and is not a solution for my peers.

Since reading “The Feedback Fallacy”, I started focusing on the outcomes I like, as opposed to qualities I believe are valuable. Where before I would say “Great comms on project X!”, now I focus on specifics: “I know what you’re up to on project X, which helps me communicate with stakeholder Y and plan resources for the project Z”

Take a pause before that email

I’m not an ill tempered person, and it takes quite a lot to get me riled up. In the pandemic however getting frustrated has been oh so much easier!

For once, there are less face to face interactions, which makes me feel removed from whomever I’m talking to. The interactions that happen over video chat feel a lot less personal, and despite regular deliberately scheduled 1:1 time it’s harder to connect with colleagues on a personal level.

Then there’s the lack of water cooler interactions between meetings. A colleague of mine correctly pointed out that before the era of video chat meetings, we’d have the time to decompress and process content between meetings with those micro-interactions. Having just a minute or two “off the record” after a large call helps process, frame, and align prior interaction. And just sharing a laugh or being able to say “well that was stressful” helps reduce the inevitable daily stress buildup.

Finally, all of the above is true for everyone else - and we’re already in a melting pot of individuals with different communication styles. People are getting frustrated, making other people even more frustrated. It’s a frustration chain reaction!

All of this led to me into a cycle of sending some snappy responses, feeling terrible after time would pass, setting up time to profusely apologize face to face, and wowing to never overreact to work stress sources again… Until the next encounter that is. It all culminated with me getting entirely too frustrated between 8:00 and 8:05 am last Thursday and taking a day just to decompress.

And that reminded of something I’ve learned years ago, and I something I would practice with rigour - until the background frustration level rose that is.

Early in my career I’ve been taught to cool down before sending that angry ping or an email – type it up, leave it in my drafts - come back to it an hour or two later.

In 9 out of 10 cases I end up deleting the message feeling relieved that an incoherent stream of hatred never saw the light of day. Most of the time when I’m angry I don’t really have a goal I’m trying to accomplish (other than inform all the parties involved of my feelings), and that’s not a great basis for professional communication.

In the remaining case, I would end up completely rewriting that email to remove the hostile tone and focus on the source of the issue instead. There are problems that are worth addressing with candor – but candor is too often conflated for the lack of tact.

And it’s hard to take a break at work - because there are often so many things to do, and so little time to do them. Which makes taking a minute to breather feel like a waste of time, when it’s one of the most productive things you can do in the long run.

So here I am, putting these thoughts into writing to remember to take a break before initiating aggressive communications – hopefully the more I think about this, the easier it gets to remember to pause, self-assess, and disconnect.